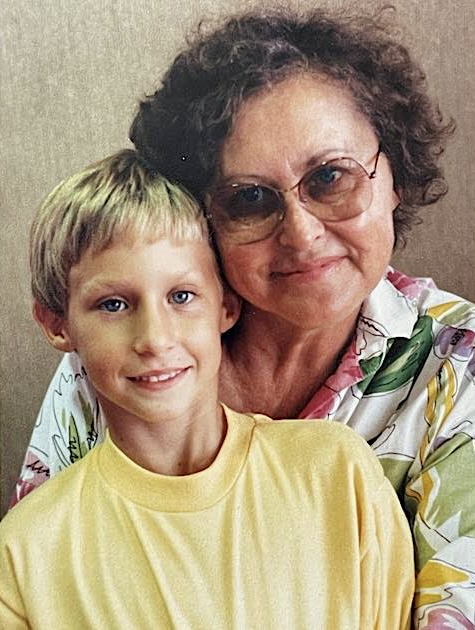

Kathleen Tunison Michel

Feb. 26, 1925–Jan. 23, 2023

At the age of eighty-four, Kathleen had an accident.

As she walked through a parking lot, she stumbled over a speed-bump and fell, face first, into the bumper of a parked car. Her injuries consisted of two black eyes, a bruised nose, and a significant gash on her forehead. (The fact that she had tripped on a speed-bump was somewhat ironic considering we were always telling her to slow down). Upon hearing the news, I immediately made a phone call. I anticipated her to be bedridden, in pain, possibly feeling a mix of embarrassment about the accident, and ashamed of the way she looked.

However, when she picked up the phone, her laughter echoed through the line, “David!” The commotion in the background suggested she was amidst some festival and was out enjoying drinks with friends. There she was, in her mid-eighties, sporting two black eyes while balancing a gin and tonic in each hand. This truly amazed me. Despite the fall that left her face marred, she chose to make the best out of that unfortunate situation. If that had happened to 99% of people her age, they would have been at home, sulking.

While many knew my Grandma as a successful businesswoman and real estate entrepreneur, there was much more to Kathleen’s story. To fully appreciate her resilience, you have to understand where she came from.

Nestled about twelve miles from Sterling, Colorado, and a mere forty miles from the Nebraska border, lies a modest farm. The area remains remote even today; back in the late 1920s, it was akin to living on the western frontier. Endless golden waves of grass stretch as far as the eye can see in every direction. Amidst this expansive prairieland, an oasis of cottonwood trees encircles a group of small buildings. Off to one side, like a watchful sentinel, stands an old, dilapidated barn. It maintains its stance today, albeit precariously. The roof bows inward and the wood siding is deeply furrowed and bleached white by the sun. The barn doors have been replaced by thick metal bars—similar to those used for highway guardrails—which have been bolted in place to deter people and animals from wandering inside.

My great-grandfather, Edgar Tunison, built this barn; and this is where Kathleen, in her youth, carried out her chores. It was her responsibility to care for the heifers, shoveling manure, milking the cows—and then separating the cream—which the family sold to purchase groceries in town. Her childhood seemed to be a perpetual bucket-brigade of sloshing milk, a task that led her to despise the smelly liquid. This labor left an indelible mark on her memory: even at the age of ninety-seven, if you asked her if she wanted cream in her coffee, she’d exclaim, “Oh, God, no!”

I once asked Kathleen who her best friend was back then and she named Betty, her older sister. However, she admitted that apart from her brother, Denny, there weren’t any other kids living out that far. Eventually, a schoolhouse was established in Atwood, and the children had to ride horses nine miles each way to attend.

Overtime, Kathleen became an expert horseback rider. This was during the Great Depression and Kathleen would help her father drive the herd across the prairie to the train-station in Sterling where the cattle could be sold and loaded onto rail cars. Kathleen had a good cutting horse which she used to keep the herd out of the river—funneling them neatly across the bridge instead.

The rock-bottom price of cattle—at eighteen dollars a head—was a figure she would never forget, as it nearly bankrupted her father who struggled to pay the land’s property taxes. Like many families during that era, they lived a hand-to-mouth existence. Nevertheless, Kathleen would remember these times as some of the happiest of her life. The Charles Dickens quote, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times… it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair,” certainly applied to life on the homestead. Kathleen learned early on that the best and worst of times—often came at once.

As a young woman, Kathleen met Alex Michel and the pair fell madly in love. Despite her fathers objections, Kathleen ran off with Alex and got secretly married in Denver. Upon Alex’s return from the war, Kathleen became pregnant, and the pair started a family of their own—with my Mom and my uncle Bob.

—————

Fast-forwarding to 1975, Kathleen, then 50, decided to start over again. Bob and Carol had lives of their own and she was newly divorced. She took the train to Denver, bringing only a suitcase of clothes and a little bunny-eared TV. She randomly found an apartment and began working the teller-line at First National Bank of Denver, enrolled in night-school, and began pursuing a college degree.

Prior to the 1970s, it was difficult for a woman to climb the corporate ladder and Kathleen was passed up for promotion time and time again. Nevertheless, she persisted, first rising to the position of head teller, then leading the bookkeeping department, and eventually moving to the loan office.

In 1975, she secured a role in the loan cage of the real estate department, supervising three individuals. She eventually rose to the rank of Vice President of the real estate department, working with real estate developers and mortgage bankers.

Later, Kathleen transitioned to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), working in the Investigation Department. Her role involved auditing failed banks and investigating fraudulent loans.

Simultaneously, Kathleen started putting her knowledge of real-estate to her own use. She obtained her broker’s license and began investing in properties for ‘fix-and-flip’ projects, decades before there was even a term for such a thing. She started with mobile homes, then moved to apartments, and finally houses. Upon retiring in ’95, she continued her real estate investments and never stopped.

————————-

Two days before Kathleen passed away, I was talking with her on the phone. I had gotten in the habit of asking her random questions about her life. And so, on this occasion I asked,

“Grandma, throughout your life, what has been your most difficult moment?”

She paused, seemingly to consider the weight of the question.

I assumed she might recount the time when she contracted polio, a perilous disease that ravages nerve cells in the spinal cord. The origin of her illness remained unknown, but it resulted in partial paralysis of her arms and legs. Doctors predicted she might never walk again. After spending six weeks in the hospital, she underwent nine months of physical therapy to regain normal movement in her extremities.

Or, I imagined, she might share the heartbreaking experience of losing a child. The baby survived merely two days and never made it beyond the doors of the hospital. Although it was never spoken of, the weight of that loss accompanied her throughout her life. Half a century later, when Kathleen’s step-daughter, Kakie Foxhoven, passed away, I accompanied Grandma to select a gravestone. I was taken aback when she ordered two: one for Kakie, and another for the baby boy she had named Donald.

Or perhaps, I thought, she might discuss Mark Foxhoven, her fiancé, who passed away unexpectedly in the middle of the night, while she slept beside him.

However, she didn’t mention any of these things.

Instead, she harkened back to a time when she was perhaps six years old. She and Betty had wandered far out into the pasture where they found a calf having difficulties. Its mother was nowhere to be seen. They tried to get the calf to its feet, coaxing it, and together, they tried to lift its incredible weight. As the sun vanished below the horizon, they persevered with their efforts into the night. With no moon to offer sufficient light, they quickly became disoriented. Two little girls—best friends—lost in that ocean of grass, doing everything they could to save that calf.

————

Such was my grandmother — tenacious, and one of the most resilient individuals I’ve ever known. She was the person I admired the most, the one I sought advice from, and the one who encouraged me to chase even the most ridiculous of dreams.

I am so very lucky to have had the honor of calling her Grandma.