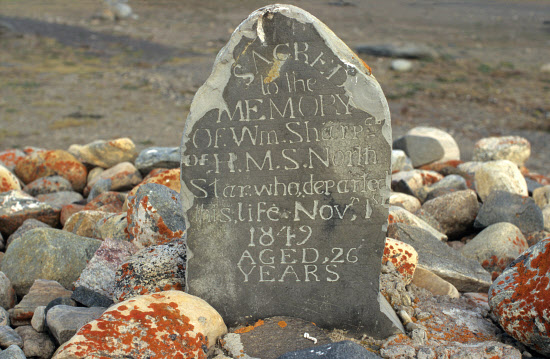

During my recent visit to Thule, Greenland I became intrigued by the areas colorful history. I stumbled upon a generic Thule Guide which makes a brief note of an “inscription plaque” left behind by the crew of the HMS North Star in 1849. I couldn’t find much about the ships history and even the old timers around Thule hadn’t heard of the “plaque” which is actually a tombstone. Anyway, I hope you find the history of the North Star as interesting as I did.

The grave is located near the Pavilion (Bldg. #1201). Park there, then cross the pipelines and walk along the ridge towards the pier. Its a two minute walk.

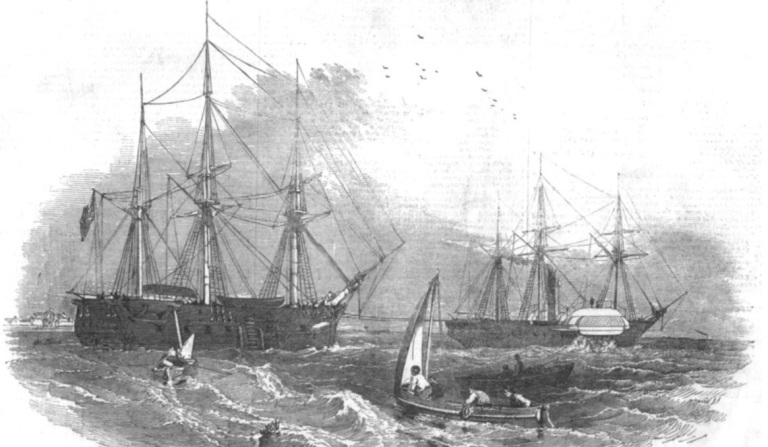

Her Majesty’s ship, the North Star, sailed tentatively through the frigid, iceberg infested waters off the west coast of Greenland. She was an old but sturdy 500 ton, 28 gun frigate with an extensive resume to boot. She had combated the Atlantic slave trade in Africa, served in the Opium War in China, and fired cannons during the first Maori War in New Zealand.

However, this was to be her first voyage into the arctic. The 63 experienced men on board must have questioned the age of the ship and the integrity of the hull but they remained optimistic. One only had to point out her name, North Star, which seemed providential; it was as if she was always destined to see the land of pack ice and polar bears.

Master and Commander James Saunders led the expedition, whose mission was to locate and resupply Captain Sir James Clark Ross. Ross had sailed from England in 1848 in search of the ill-fated Franklin Expedition. Sir John Franklin with his two mighty ships, the Erebus and Terror, had been missing in an unexplored area of the arctic for three and a half years and the Admiralty was gravely concerned of their whereabouts. In essence, the North Star was sent to search for the searchers.

If Saunders was not able to locate Ross or Franklin, he was ordered to deposit his stores along several named areas of the arctic coast and return to England before the onset of winter. Under no circumstances was the North Star to risk being beset by the ice and forced to winter-over.

Unfortunately, the sea-ice in Melville Bay was thick and unruly that year. While sailing around the thicker ice-fields they spotted several small boats approaching. They were the lifeboats from the whaling vessel Lady Jane. The crew had abandoned their ice-ravaged ship, now sunk. They brought word that two other whaling ships, the Superior and the M’Lellam, were involved in the incident and had shared the same watery grave. The crews were on their way to Greenland’s Danish settlements where they hoped to find assistance. The captains traded letters and the men went their separate ways.

Just one month later, they met the lifeboats of yet another whaler, the Prince of Wales, also sunk by the ice. The news that, not one, but four ships and been wrecked, must have been a sobering reminder of what the sea-ice was capable.

On July 29th, during the height of the summer season, the vigilant officers of the North Star observed the surrounding sea-ice closing in upon them. The crew acted quickly and positioned the ship in a natural cul-de-sac of a large ice floe. The floe acted as a shield, protecting the ship from the immense pressure of the encroaching ice. Although temporarily free of the immediate threat, they were now imprisoned in the pack, and at complete mercy of the wind and current.

While adrift they spotted a massive iceberg ahead. They estimated its size to about a mile in length.

As they neared, they could see that the berg was unmoving, evidently grounded, and yet the sea-ice was hurtling them ever towards it. There was nothing for the men to do but await their fate. As luck would have it, they passed along the easternmost edge of the berg with just 300 yards to spare.

The helpless ship drifted northwards in this precarious position for the better part of two months, when finally, in late September a small open stretch of water was observed in Wolstenholme Sound.

Despite a heavy gale, all men were called on deck and the sails hoisted. The wind caught and the ship lurched forward, bashing her way through the ice, and finally, bursting through into open water. Master Saunders reported after the event,

“I cannot sufficiently express the heartfelt joy that every man and officer felt at this unexpected and miraculous dispensation of Providence in releasing us from the ice in this extraordinary matter in which we were; for if we had not got in here, I fear very few if any of the crew would have survived the winter, as it is more than probable the ship would have gone to pieces…”

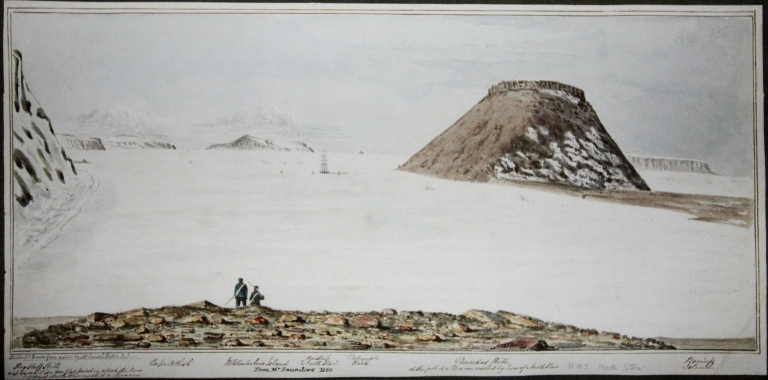

The North Star then made anchor just south of the fjord, in a protected cove known today as North Star Bay. The pack-ice acted as a barrier, trapping them inside the harbor. The men were about to face the realities of an arctic winter, cut off from the rest of the world, farther north than any British ship had ever attempted.

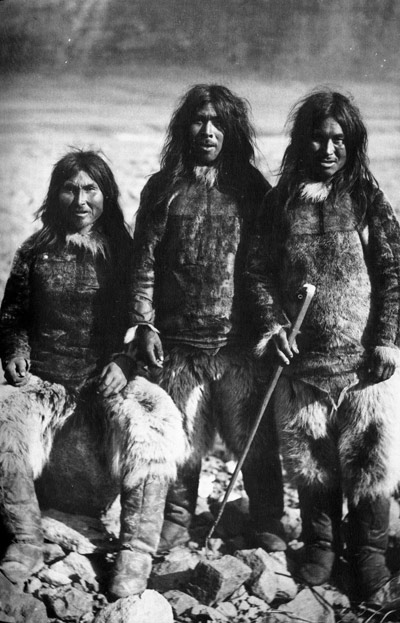

Despite their remote location, it must have come as a surprise when the men discovered they had neighbors. A small family of Inuit lived in a sod igloo near the base of the table-topped mountain (which the sailors called Dundas Hill and the natives called Umanaq) and another family lived about 12 miles up the fjord.

The natives visited the ship on several occasions, but as was customary of British sailors of the day- they looked down upon the Inuit as mere destitute savages, nothing to be learned from or gained. Saunders describes them,

“Here we found a settlement of Esquimaux…They appear very harmless people, but possessing less ingenuity than any race of beings I have ever yet seen… They do not know the use of boats, and their only weapon appears to be a small spear, which they carry in their hand.”

As the temperatures plummeted, the ship was made ready for winter. When the bay froze, they shoveled snow around the vessel to add as insulation. They dug a ditch, or a moat, around the ship to dissuade any polar bears that might be lurking about.

Hunting forays into the hillside produced little. They were told that muskox and reindeer roamed in great herds but never a one was seen.

They were able to shoot and kill about 50 rabbits, the fresh meat must have come as a welcome reprieve from their usual diet of hard tack- a biscuit made of flour and water that was difficult to eat without first soaking in water.

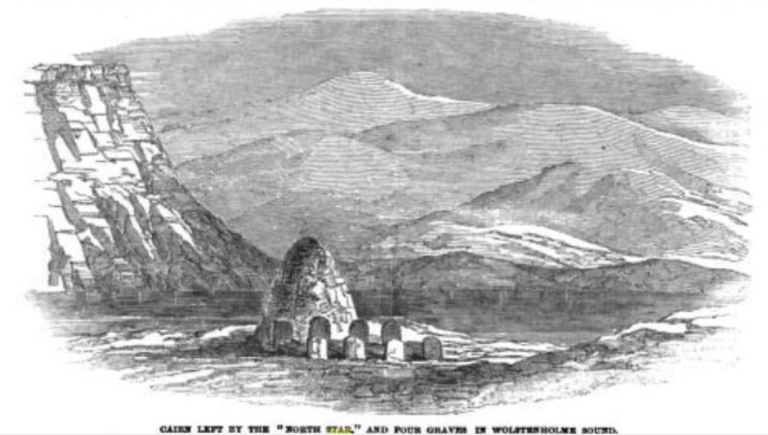

On October 31st the first man died. His name was William Sharp and he was just 26 years old. His body was carried 1.5 miles from the ship and buried on shore. A crude tombstone was erected to mark the spot. It still stands today, although it’s been moved and now rests on top of the cairn nearby. The following day William Sharp’s clothes were sold at auction. The men weren’t about to bury perfectly good clothing, especially in those temperatures.

Exactly HOW Mr. Sharp died seems a matter of speculation. Apparently in the 19th century when a man died on ship, he was simply dead, and that was the end of the matter.

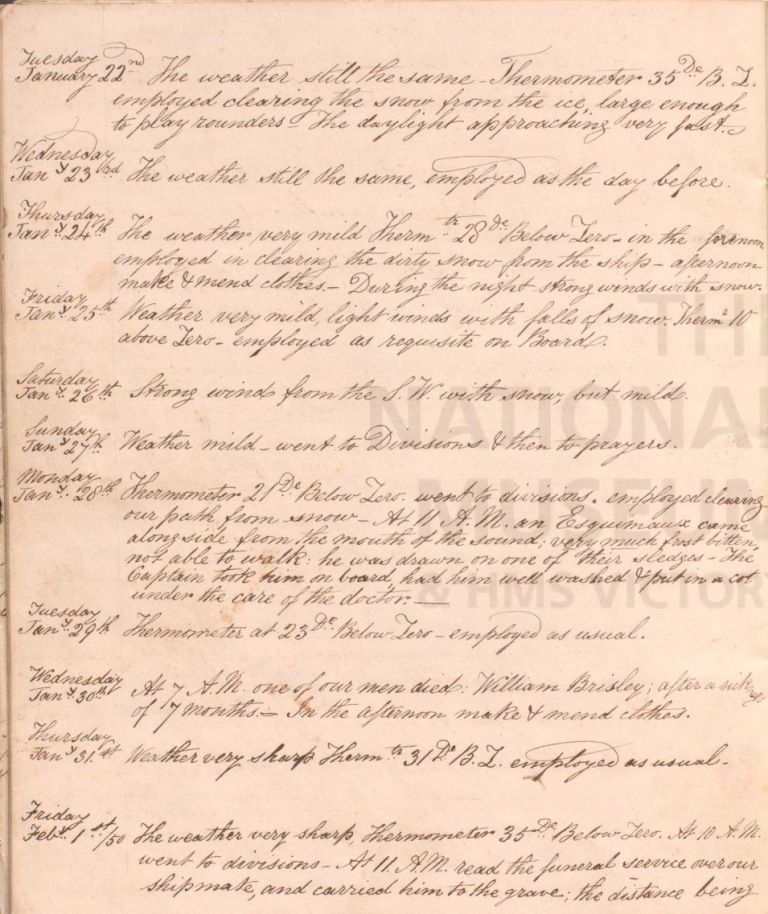

As the winter progressed the men were kept busy. They fed the stoves coal (which they brought from England) to keep the ship warm. They built a road out to a nearby iceberg where they mined ice for water.

They cleaned the dirty snow and human waste out from around the ship and they mended their clothes.

For entertainment they climbed the surrounding hills (as men and women still do today) and built snowhouses for personal use.

*Courtesy of the Royal National Archives

Almost every evening, if the weather was decent, they cleared the snow off the sea-ice and played ‘rounders’- which was an early form of baseball.

On special occasions the men opened the ‘Theater Royal’ and amused themselves by performing ‘White Horse or Love in a Mist: a comedy in three acts’ and ‘The Citizen: a farce in two acts’. The men dressed up as women and played the female characters as well. They also had impromptu masquerades- which had them singing and dancing long into the night. It should be mentioned that the ship was handsomely equipped with brandy, rum, and red and white wine.

As the winter continued the temperatures dropped ever farther. The crew of the North Star saw temperatures as cold as 63 below Fahrenheit, which at the time, was believed to be the coldest temperature ever recorded.

On January 28th, a group of Inuit approached the ship. One of them was frostbitten badly, unable to walk and drawn on their sledge. The Captain took him aboard, had him bathed, and placed him under the care of the doctor.

His health improved dramatically for several weeks and his legs nearly healed, but he succumbed to a pulmonary sickness and died shortly thereafter. Could it have been the same sickness that had claimed William Sharp’s life? Before the North Star would set sail again, three more of her men would die. None of those deaths were attributed to the cold. Some have speculated scurvy.

On August 1st, the bay had melted enough for the ship to break free of her 10 month icy imprisonment. Captain Saunders was determined to fulfill the ships duties by delivering the provisions to the lost men of the Franklin expedition. However, he wouldn’t find them. After much searching, they placed the supplies at Navy Board Inlet on the north side of Baffin Island and set sail for England.

The tons of provisions left by the North Star were never used. Years later it was discovered that the cache had been found and looted by natives.

The 1850 voyage of the North Star achieved absolutely nothing in the annuals of polar history. However, only four men died during the perilous journey. Sir John Franklin’s men were not so lucky, as all 129 men were never seen alive again.

References:

I.G. Aylen’s ‘HMS North Star and the Birth of Thule’ (April 1987).

R. J. Cyriax’s ‘The Voyage of the North Star, 1849-50’ in ‘The Mariner’s Mirror, Vol. 50 No. 4’ (1964)

‘John O’Groat’s Journal’ SG & SGTL Page 43 (9 Feb 1850)

James Saunders’ ‘Proceedings of HMS North Star’ in ‘Accounts and Papers of the House of Commons’ (4 Feb-8 Aug. 1851)

Samuel M. Smucker’s ‘Arctic Explorations and Discoveries During the Nineteenth Century’ (1857)

Benjamin B. Norrington’s ‘Log book of the HMS North Star’ (1849-50), Courtesy of the Royal Naval Museum

It’s been many years since Dundas, but I will always remember Greenland. Worked with RCA on a summer cleanup utility crew out of New Jersey. We climbed Mt. Dundas one evening, explored the ice cave under another midnight sun, and went to the garnet fields another time. Traveled in the back of an IH pickup!

We also got to meet some Inuit. We saw an abandoned sod house at Dundas. Could it have been there since the time of North Star? (Also lots of BIG flies).

Didn’t see any rabbits.